On the Figure That Doesn’t Belong

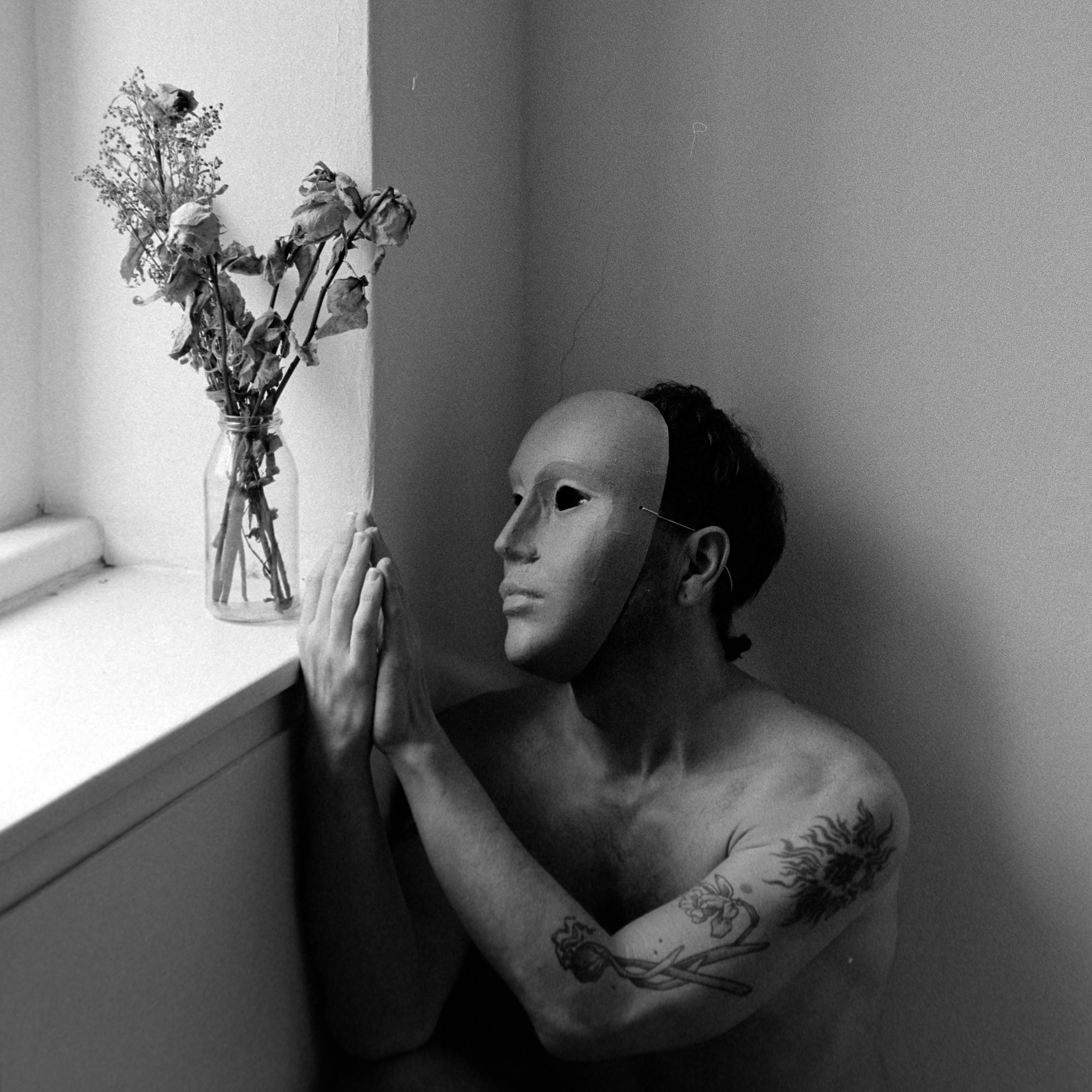

Untitled (Mask), 2023

Feminist art began, necessarily, with a refusal. A refusal of objectification, of erasure, of exclusion. It turned its back on the tradition of the male artist painting the female nude. It turned its face to the camera, to the performance, to the wound. In this refusal, the male body—especially the male-presenting body—was often cast as the enemy. Or worse: irrelevant.

But art does not obey ideology for long. And bodies, like ideas, slip through definitions.

The male-presenting body has not been central to feminist art, but it has never been entirely outside it. It haunts its edges. It presses against its rules. It asks uncomfortable questions: What does it mean to be read as male in a space of feminist politics? Is the male-presenting body always a sign of power? What does it mean when that body is vulnerable, disobedient, self-conscious, soft?

Queer-feminist art reopens these questions. It is less interested in who the body is, and more concerned with what it does. It understands gender not as biology, but as behavior. Jack Halberstam reminds us that masculinity is not property—it is residue, posture, a flicker of intention. Something anyone might put on, discard, inhabit briefly, or get stuck inside.

Del LaGrace Volcano photographs bodies mid-transformation, mid-declaration, mid-collapse. Their portraits are not statements—they are thresholds. Masculinity becomes a trace, not a destination. A thing tested against the surface of the skin, the camera, the viewer. Volcano’s work doesn’t document the male body—it disorients it.

In Intimation, I argued that the self-portrait is not revelation but construction. The male-presenting body, too, constructs itself before the lens—often in tension with the role assigned to it. A body performing not strength, but uncertainty. A body in makeup, or in mourning. A body that chooses softness not to parody the feminine, but to escape the tyranny of masculinity.

This is not about reversal. It is not the feminization of the male body. It is the refusal of the binary altogether.

Pierre Molinier’s self-portraits—stockings, prosthetic limbs, erotic confusion—offered a drag of another kind. Not the camp of exaggeration, but the fetish of fragmentation. Molinier didn’t want to be one thing. His male-presenting body posed not as author, but as object—split, masked, multiplied.

To inhabit a male-presenting body in feminist space is to risk suspicion. But it is also to offer something rare: the possibility that even the dominant form can be destabilized from within.

Cassils takes the muscular body—so often a monument to male power—and turns it into an event. They train, sweat, sculpt, bleed. In performance, the skin breaks, the body exhausts itself. Masculinity is not performed—it is disassembled in real time.

There is a kind of queerness that does not shed its masculinity but retools it. Not the performance of the hyper-masculine, but its erosion. A slouch instead of a stance. A gaze that refuses to dominate. A gesture that falters.

Feminist art, at its most rigorous, is not about identity. It is about critique. And critique must be porous, reflexive, disobedient. It must allow the unexpected figure to enter the frame—not to dominate it, but to reshape its balance.

As José Esteban Muñoz reminds us, queerness is not a position—it is a horizon. Something not yet here, but already felt. Perhaps the male-presenting body, made strange, uncertain, speculative, is part of that horizon. Not a restoration of power, but a misreading of it.

The male-presenting body, when it appears in queer-feminist art, is not a return of the patriarch. It is a ghost. A witness. Sometimes even a collaborator.

This body is not there to be redeemed. It is there to be unmade.

—Daniel Hill, 2025